Now that Term 3 has come to an end, I am again analysing the data from Year 7’s evaluation of their learning. Year 7s complete a weekly reflection on their learning as well as an end-of-term evaluation. Their end-of-term evaluations gives me an idea on how they feel about how I structure their learning activities so that I can adjust the next term’s learning accordingly.

For Term 3 our project based learning focus has been on newspapers. For 8 weeks, students deconstructed the language features of news articles and put together a range of articles on the Olympics, the Paralympics and other newsworthy items. Some of these articles were written in groups and some were written individually. Year 7s then selected some of these articles to put together a newspaper using Microsoft Publisher. Each news article involved students revising the article at least twice using the goals, medals and missions structure of feedback. In Term 3 we also did science experiments on Tuesdays that were based on sport science under the theme of the Olympics. For half of Term 3 the class worked with Year 6 students from Merrylands East Public School on Murder under the Microscope, an online environmental science game where students acted as forensic scientists to solve a crime involving the pollution of a catchment area. One new activity I introduced in Term 3 were weekly revision quizzes. These quizzes were essentially thirty-minute pen-and-paper-exams that tested Year 7’s understanding of concepts we have learnt during the week. However, they were allowed to refer to their books if necessary (I just think this is more realistic of real life. When in your life do you come across something you can’t do and force yourself to sit there for 30 minutes without makin any attempt on finding out how to do it. I also think it gives a purpose to students’ book work and instil in them a routine of what revision and studying looks like and feels like.) With these weekly revision quizzes, students mark each other’s work. The quiz is divided into concept areas such as algebra, language features of newspapers and scientific investigations and marks are awarded separately to each concept. Students then look at their performance for each concept area and write a short reflection on what they are good at and what they need to improve on.

So this week, Year 7s completed an end-of-term evaluation of their learning on Survey Monkey.

Term 3’s evaluation consisted of these questions:

- What is your favourite subject?

- What makes this subject your favourite subject? What do you like about it?

- Rate how much you enjoy the following activities (students choose from “I enjoy it”, “I find it OK” and “I don’t enjoy it”

- Project work

- Science experiments

- Maths and numeracy

- Murder under the Microscope

- Edmodo homework

- Rate how much you learn from the following activities (students choose from “I learn lots from it”, “I learn some things from it” and “I barely learn anything from it”)

- Project work

- Science experiments

- Maths and numeracy

- Murder under the Microscope

- Edmodo homework

- Do you want to continue doing project work on Mondays and Fridays?

- What are 3 things you have learnt from the newspaper project?

- List 3 things you want to improve on next term.

- If you were the teacher of 7L, what would you do to improve learning for the class?

So here are the results:

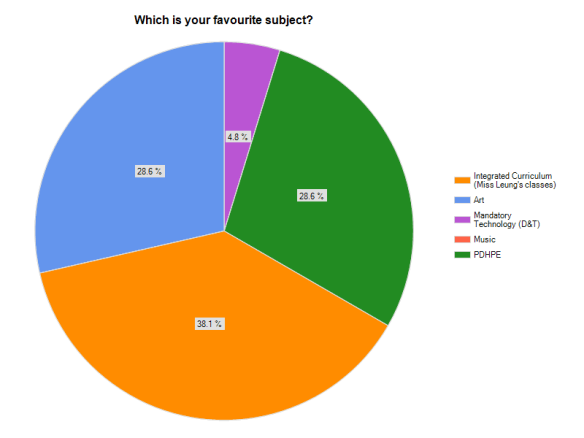

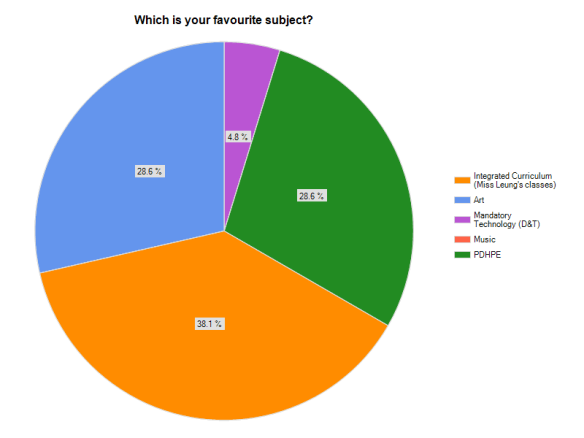

What is your favourite subject?

I’m going to conclude by just saying it takes a lot to beat PDHPE as students’ favourite subject.

Reasons why integrated curriculum is their favourite subject

Below are some of the responses from students who chose integrated curriculum as their favourite subject:

Because we get to have fun in those classes and do interesting stuff.

The experiments we do and how all the subjects are put into one class.

It involves technology.

There are so many opportunities to do fun activities and showing people my work.

Some of the major themes from this question are that students find integrated curriculum classes “fun”. They also like using technology such as laptops and tablets for their learning, as well as having 5 subjects embedded into one class. Some students enjoy having their work showcased on the class blog.

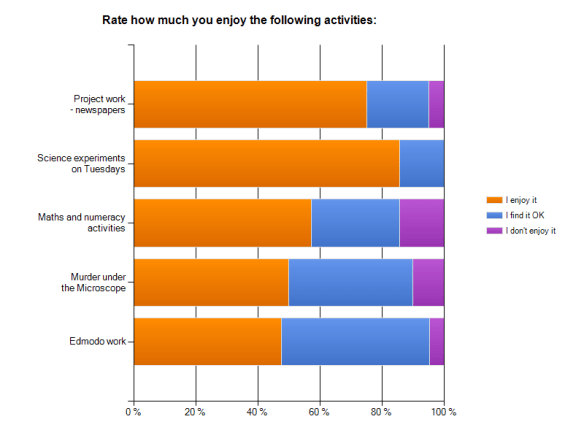

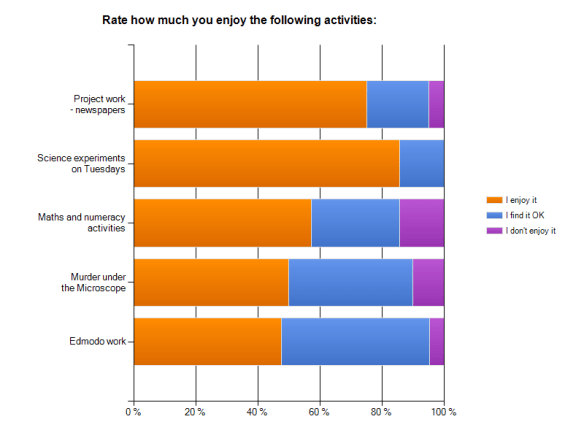

Rate how much you enjoy the following activities

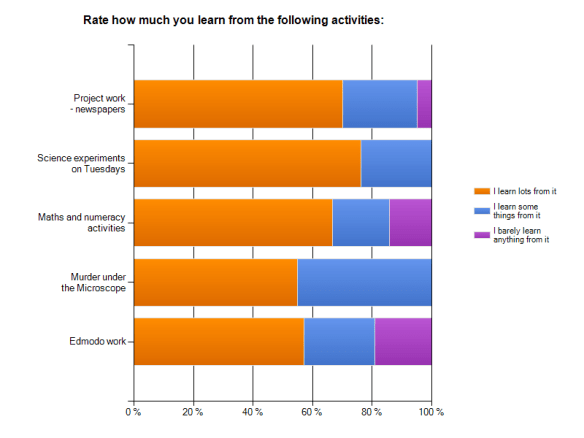

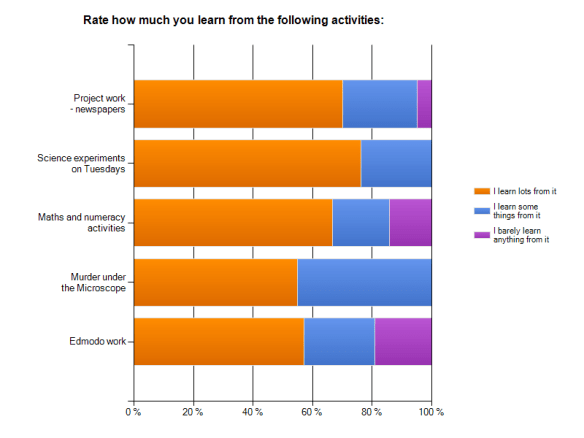

Rate how much you learn from the following activities

What are 3 things you have learnt from the newspaper project?

A word cloud was created for students’ responses to this question where the larger the word in the word cloud, the more frequent that word appeared in the responses.

List 3 things you want to improve on next term.

This term was the first time students wrote features of effective team work for their improvements for the following term. In previous end-of-term evaluations, students often listed relatively superficial things they’d like to improve on such as write faster or finish work faster. For this term’s evaluation, the majority of students listed features of team work skills such as listening to other students, working as a team and self control. Many students also identified specific areas of content they’d like to improve on such as algebra or types of scientific variables. This is in contrast to how they listed their improvements in previous evaluations where many students wrote umbrella terms such as numeracy or literacy.

For me, this shows an increased level of maturity in the way they assess their learning. While I can’t attribute the cause of this change to any particular strategy I’ve used, I do have a strong feeling it is to do with the goals, medals and missions structure of providing feedback in their PBL tasks and also their weekly reflections on their revision quizzes. Over a term I think most Year 7s have increased their self-awareness of their own learning.

What have I learnt?

For most of this year I have been experimenting on strategies on guiding students to become more effective learners. The PBL initiatives, the goals-medals-missions structure of feedback, the weekly revision quizzes and weekly reflections of learning have all been things aimed at allowing my students to further develop into effective learners. While I always knew that features such as working together and being self-aware of your strengths and areas for improvement are equally important as understanding subject-specific concepts, I think teaching my Year 7s for 5 different subjects have really made that clear to me. When I think back to how I structure my learning in previous years for my science classes it has always been more focused on content rather than developing students into effective learners. When I do eventually return to teaching science classes only, the way I will structure learning for those classes will be very different to how I used to structure them. Teaching an integrated curriculum has so far been one of the best professional learning I’ve had.